The Mission: Impossible franchise has never just been about heart-stopping stunts or Tom Cruise dangling from cliffs and aircraft—it’s also a masterclass in cinematic craftsmanship. One of the often overlooked but absolutely essential components to this franchise’s visceral thrill is its remarkable use of cameras and lenses. From classic Panavision 35mm film cameras to cutting-edge digital rigs like the Sony VENICE and the Z CAM E2-F6, the franchise is a visual evolution worthy of its own action-packed story. Thanks to a recent reveal from Panavision, and our own deep dive (complete with detailed slides breaking down camera and lens packages per film), we can now explore how each chapter in this saga was captured—frame by breathtaking frame.

Film First: The Panavision Legacy

At the heart of the visual language for most of the Mission: Impossible films lies the magic of celluloid. The franchise proudly embraced film for the majority of its installments, preserving that organic, gritty, and immersive feel that digital has often struggled to replicate. The dominant lens throughout much of the franchise is the revered Panavision C-Series Anamorphic, a staple in high-end cinematography since 1968. Known for its compact, lightweight design, this lens series is prized for its pronounced anamorphic flares, organic feel, and flattering bokeh. Its graduated depth of field and predictable performance at all apertures make it a go-to choice for DPs who seek both character and consistency. Simply put: it’s cinematic alchemy in glass. Complementing these lenses was Panavision’s workhorse film camera—the Millennium XL, and later the Millennium XL2. This camera brought modern ergonomics to traditional 35mm filmmaking, offering sync-sound capability, modular design, and compatibility with all Panavision lenses. Whether mounted on a Steadicam, handheld, or attached to a vehicle, the Millennium XL2 offered both versatility and uncompromised image quality. Explore the ‘Film’ movies below:

The Panavision Millennium XL2 and the Z CAM E2-F6—two radically different cameras—both became heroes of this franchise. One delivered grandeur, the other intimacy. One relied on celluloid, the other on sensors. But both served the story, and that’s what truly matters.

The Shift to Digital: Mission: Impossible VII and VIII

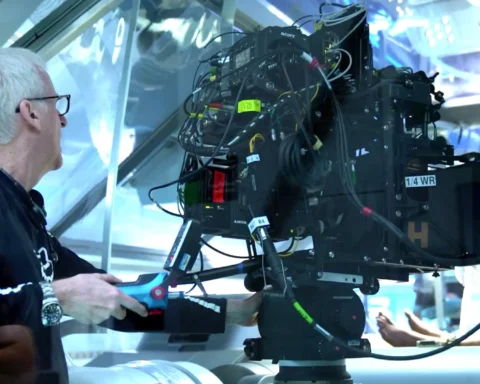

While film dominated the franchise for decades, Mission: Impossible VII (Dead Reckoning – Part One) marked a major turning point. For the first time, digital cinematography took center stage. The Sony VENICE, known for its full-frame sensor, dual native ISO, and incredible color science, became the main camera, delivering stunning resolution and high dynamic range imagery worthy of the franchise’s legacy. But the real digital revolution came from an unexpected source: Z CAM. In “Tom Cruise, the SnorriCam, and the Z CAM Revolution in Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning”, we detailed how this Chinese-made, compact powerhouse became integral to the franchise’s most audacious shots. The Z CAM E2-F6, a full-frame, 6K-capable cinema camera, was used extensively in both Mission: Impossible VII and VIII, particularly for high-risk, high-speed action scenes. Explore the slides below:

Having watched the IMAX release ourselves, we can confidently say the Z CAM looks spectacular!

The Z CAM Hero Moments

In “Z CAM E2-F6: The Small Beast Behind the Big Action of Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning”, we explored how this underdog camera was mounted on motorcycles, inside fighter jets, and even used with SnorriCam rigs directly attached to Cruise himself. Its compact size and cinematic image quality allowed DPs to capture real action, in real environments, with minimal compromise. You might assume a smaller camera like this would falter on the IMAX screen, but you’d be wrong. Having watched the IMAX release ourselves, we can confidently say the Z CAM looks spectacular. Whether capturing cockpit interiors or death-defying freefalls, the E2-F6 held its ground against the VENICE and even legacy film formats. In fact, it’s been the main action camera across many sequences. In “The Action Camera Behind Mission: Impossible 7″, we documented how the Z CAM was used in chase scenes, car interiors, and close-quarters combat—proving once and for all that size doesn’t limit cinematic capability. Perhaps the most unforgettable example of its strength was in the train crash sequence, detailed in “Mission: Impossible 7: Six Z CAM Cameras to Capture Real Train Crash”. Here, six Z CAM E2-F6s were rigged to the train itself, capturing every twist, snap, and explosion in stunning 6K resolution—real, raw, and unfiltered.

The Panavision–Z CAM Arc

If we step back and look at the full cinematic arc of the franchise, it’s clear that Panavision and Z CAM represent the two poles of its visual identity. Panavision, with its legacy film equipment and character-rich lenses, defined the early DNA of Mission: Impossible. Z CAM, with its rebellious form factor and agile capability, defines its modern edge. It’s poetic, really: the Millennium XL2 and the Z CAM E2-F6—two radically different cameras—both became heroes of this franchise. One delivered grandeur, the other intimacy. One relied on celluloid, the other on sensors. But both served the story, and that’s what truly matters.

Final Thoughts

The cinematography of Mission: Impossible has always been part of the franchise’s magic. Now, thanks to detailed insights from Panavision and firsthand observation of recent films, we can fully appreciate how much care, innovation, and respect for tradition goes into capturing every single shot. Whether it’s Tom Cruise sprinting across the rooftops of Paris on 35mm film or leaping from a plane captured by a Z CAM in IMAX, one thing is certain: these movies look the way they do because of the gear—and the brilliant people—behind the camera.

2 questions:

– what lenses specifically were used with the z-cam?

-how come all the pictures you use say auto panatar lenses, but that’s not listed in any of the descriptions?

1) Zeiss Compact Primes.

2) Because the C-Series is the new iteration of the auto panatars. Go to the Panavision website and you will see it.

CHEERS!