A newly published Nikon patent titled Image Sensor details a pixel architecture that could allow the same chip to function as both a global shutter and a rolling shutter sensor. If implemented, it could open doors for hybrid capture modes where the camera automatically selects the best shutter behavior depending on whether you are shooting stills, video, or high dynamic range content. The technology is still on paper, but the fact Nikon continues to file continuations of older applications tells us the company is actively protecting this intellectual property. For filmmakers, the ideas described in the document are worth unpacking in plain English.

The problem with shutters: global vs rolling

Every digital camera sensor today falls into one of two camps.

-

Rolling shutter. The sensor scans the image row by row, a bit like a photocopier bar moving down the frame. It’s efficient and fast for video but creates the well-known “jello effect” where vertical lines bend during quick pans. LED screens or flash lighting can also cause banding.

-

Global shutter. All pixels start and stop exposure at the exact same instant. That solves skew and flicker problems, but it often comes with penalties: lower dynamic range, more noise, or slower readout speeds.

Most consumer cameras only give you rolling. Some specialized cinema or machine-vision sensors offer global, but you typically have to buy into one or the other.

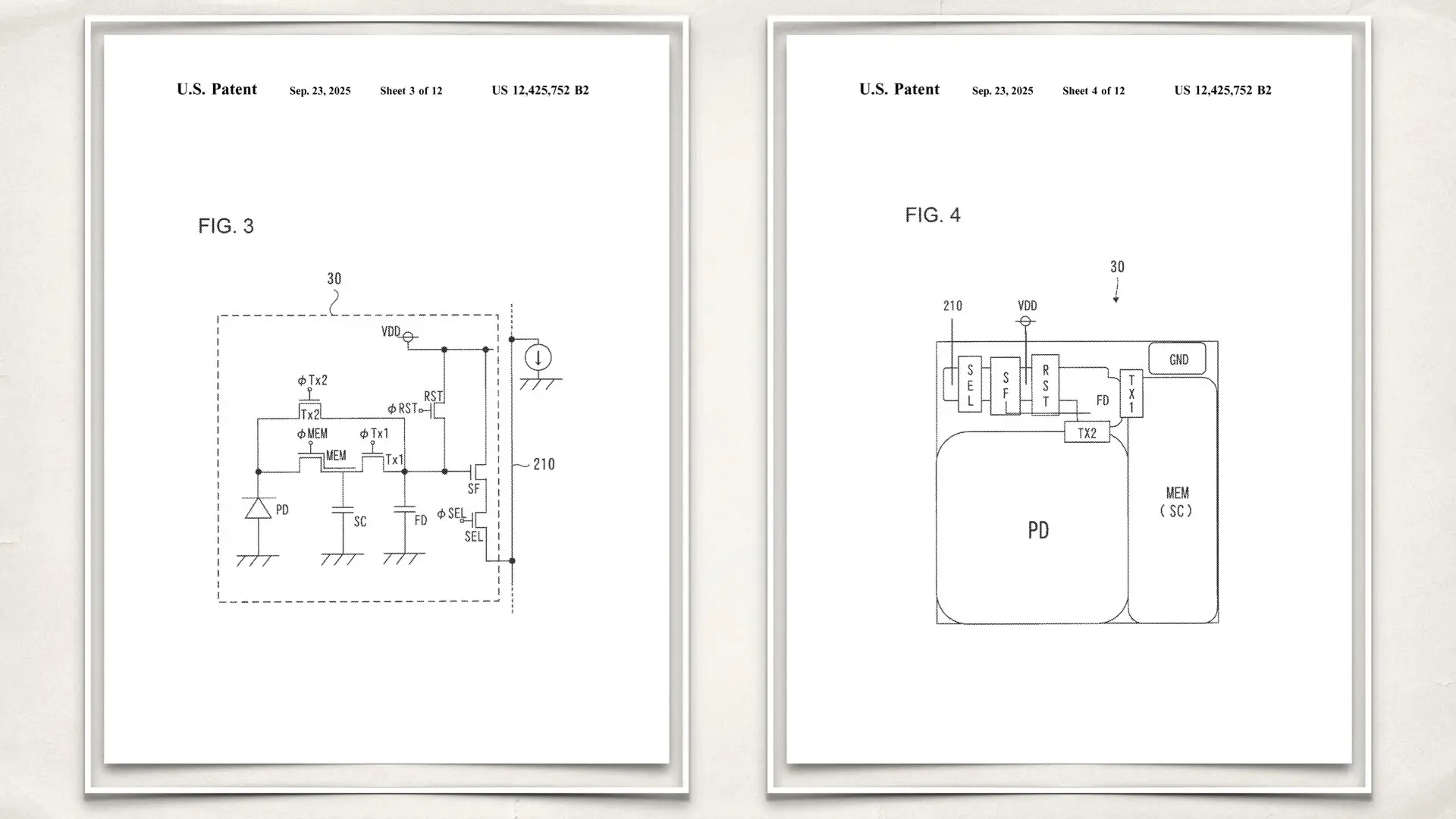

Nikon’s idea: give each pixel two doors

The core of Nikon’s patent is surprisingly elegant. Each pixel has two possible paths for the electric charge generated by light:

-

The fast door. A direct route from the light-sensitive diode to the readout circuit. This is quick and simple, ideal for rolling shutter operation.

-

The storage door. A detour through a tiny side capacitor that can temporarily hold charge. This path allows all pixels to stop exposure at the same moment, enabling global shutter behavior. It also doubles as an overflow bucket, catching extra electrons in bright conditions to extend dynamic range.

With both doors available, the sensor controller can decide how to run the chip. It is the same hardware, just operated differently.

How it works in practice

-

Global shutter mode. All pixels expose at the same time. When exposure ends, each pixel’s charge is quickly moved into its storage capacitor. From there, the image can be read out row by row. The captured moment was identical across the frame, even if the reading process takes time.

-

Rolling shutter mode. The controller skips the storage step and instead reads rows sequentially. It can choose the direct path for speed, or the storage path if it wants to use the overflow capacitor for highlight handling.

This dual-path design even allows multiple rolling variants, as Nikon describes in detail: one where overflow is caught for more dynamic range, one where charge is moved step by step, and one where the direct path is used exclusively.

Will shooters be able to flip a switch?

This is the question many readers ask. The short answer is: probably not.

No Nikon, Canon, or Sony body today gives users a menu toggle between global and rolling. The camera firmware usually makes that decision. For example:

-

Stills or burst shooting could trigger global shutter automatically to avoid skew.

-

Video recording may default to rolling for efficiency.

-

HDR or difficult lighting scenarios might activate the capacitor path for extended range.

The patent makes the flexibility possible. Whether Nikon exposes it as a manual option or keeps it hidden behind automatic modes will be a product decision. Right now, the safest assumption is that the choice would be invisible to the user.

What about dynamic range?

The patent does not reveal any hard numbers for dynamic range. There are no stop counts or comparative charts. What it does describe is the mechanism: each pixel includes a small storage capacitor that can catch overflow from the main photodiode. Instead of clipping highlights when the pixel is full, the excess charge can spill into this side bucket and then be read out along with the main signal. In theory, that gives the sensor more headroom before highlights blow out, which is especially useful in HDR scenes. In practice, we will only know the true dynamic range once Nikon implements this in real silicon. Patents are about protecting the idea — the final performance depends on how it is manufactured and tuned.

Why it matters for filmmakers

If Nikon commercializes this design, it could bring several advantages into a single camera body:

-

Cleaner motion. Global shutter capture for fast pans, sports, or VFX plates where geometry must remain accurate.

-

Dynamic range. Overflow into the side capacitor means highlights can be preserved rather than clipped.

-

Lighting stability. LED panels, strobes, and mixed-frequency lights become less problematic with global control.

-

Efficiency. Rolling shutter is still available when long takes or throughput matter more than motion integrity.

Instead of choosing one compromise forever, filmmakers could get the benefits of both approaches on demand, even if the camera itself makes the call.

Evolutionary, not revolutionary

It is worth putting this in perspective. The concept of hybrid shutters is not unique to Nikon; Sony and Canon have also explored similar technologies. What makes Nikon’s filing interesting is the clean way it integrates two charge paths per pixel with an explicit plan for HDR extension. This is not the birth of a brand-new sensor category, but it is an evolutionary step that could make global shutter practical in mainstream bodies without forcing trade-offs. And given Nikon’s cinema ambitions: from the Z-mount to the ZR ecosystem with RED, such a sensor architecture fits neatly into the bigger picture.

What we still do not know

-

Sensor size and pixel pitch. Nothing in the patent specifies whether this is APS-C, full-frame, or larger.

-

Readout speed. The diagrams describe timing, but not actual frame rates.

-

Noise performance. Adding extra capacitors can sometimes increase noise or reduce efficiency.

-

Product timeline. Patents often take years to reach production, if at all.

Nikon’s Sensor Innovation in Context

To understand just how ambitious Nikon’s new patent is, it helps to see it as part of a larger push inside Nikon’s imaging division—one laid out across several YMCinema articles:

-

“Nikon ZR: RED Future of Cinema” covers Nikon’s bold step into cinema cameras with the ZR and its integration of RED’s ecosystem. YM Cinema

-

“Nikon’s New Sensor Patent Targets Faster Readout and High-Resolution” analyzes how a layered or stacked design can speed analog readout and enable ultra-high resolution. YM Cinema

-

“Nikon Large Sensor Cinema Camera Technology” presents Nikon’s longer-term vision for big sensors in cinema bodies.

-

“Nikon’s New Patent Hints at Cinema-Ready IR Sensor Innovation” shows how Nikon is exploring multiple fronts (including infrared) in sensor R&D.

This new dual-path pixel patent dovetails with those earlier advances. Whereas previous Nikon patents and discussions have emphasized faster readout, higher resolution, and emerging infrared/Cine sensor capabilities, this one adds a fundamentally new axis: flexible pixel-level shutter behavior. It doesn’t just make sensors faster or more sensitive—it gives them a choice in how they capture motion.

In other words:

-

The prior sensor patents laid the plumbing (speed, stacking, readout architecture).

-

This patent adds the control valve—letting each pixel choose “which shutter mode” to use.

-

Together, they hint at a future Nikon cinema sensor that is high performance and highly adaptable.

For filmmakers, that means Nikon could be building sensors that not only match or challenge Sony, Canon, or RED in specs, but also introduce intelligent behavior that tailors shutter mechanics per scene.

Takeaway

Nikon’s “Image Sensor” patent is not a revolution, but it is a significant signal. By designing pixels with two possible doors, Nikon lays the groundwork for sensors that can perform as both global and rolling shutter, with added dynamic range benefits. For filmmakers, the practical outcome could be cameras that quietly switch between modes depending on the scene, delivering global shutter performance when motion integrity is critical and rolling shutter efficiency when throughput is key. It may not be a headline-grabbing revolution, but it is exactly the kind of behind-the-scenes innovation that shapes the next generation of cinema cameras.