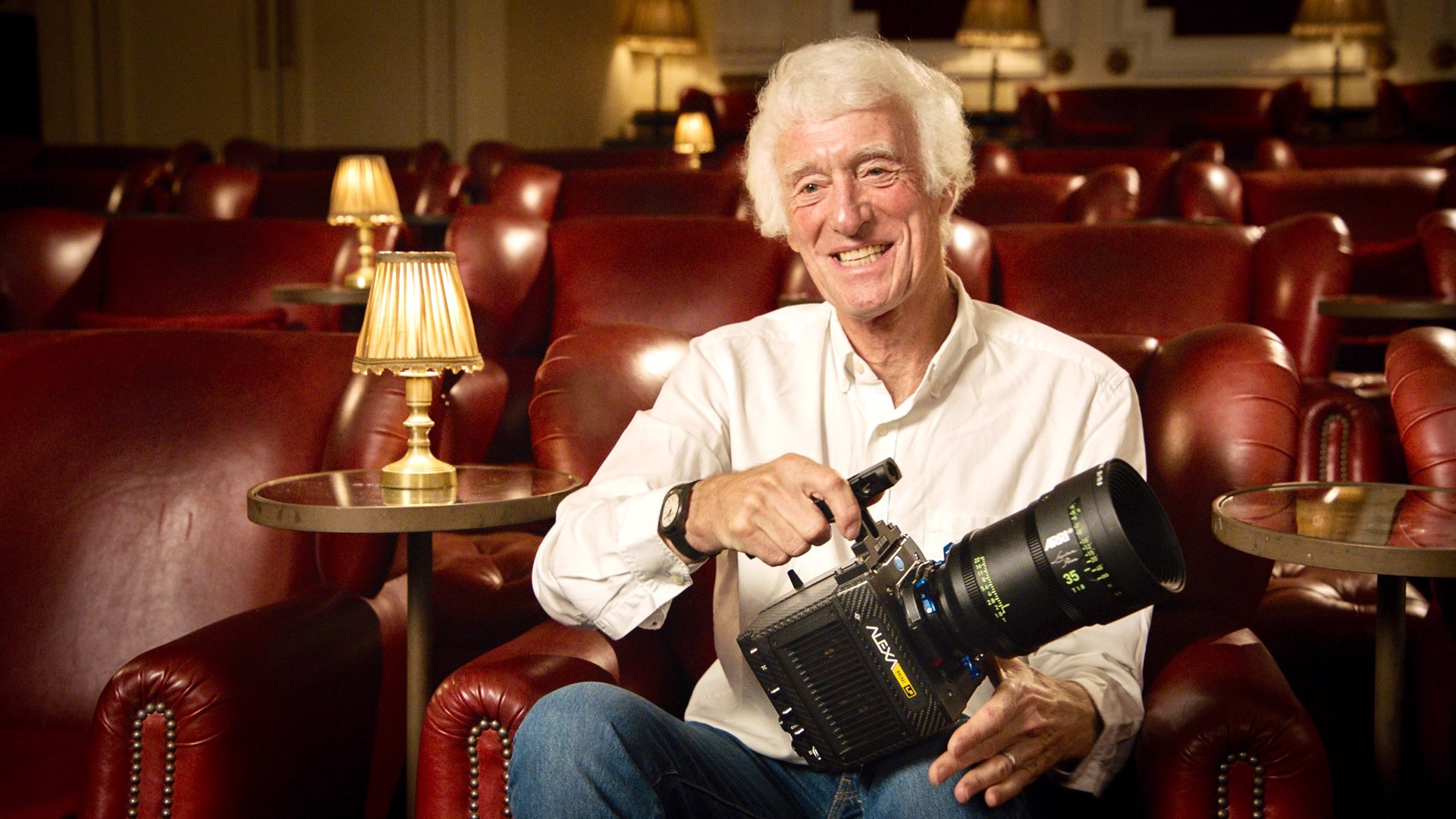

Roger Deakins talks about the cinematography challenges behind one of his most ambitious films, from a DP point of view. The tricks behind 1917 and the difficulties of shooting long takes. Read below.

Long Take as a tool to enhance realism and immersiveness

There is nothing like a long take to demonstrate and emphasize realism. You can ask Emmanuel Lubezki A.S.C., A.M.C, and he will confirm that:-) By the way, according to Lubezki, the long takes are no more than cinematography tricks to make the shot more dangerous and mysterious. Moreover, these techniques deliver an elevated immersive experience to the audience. However, those “tricks” might be turned as obsolete since a lot of cinematographers use them. Nevertheless, the film 1917 was also led by this concept. However, the 1917 production environment lacking blue (or green) screens, based mostly on natural lights and live-motion effects, was constituted a significant challenge for “long take” executions. Indeed, 1917 faced multiple challenges in order to deliver one continuous, uninterrupted shot.

The Art of the Long Take

We have written an in-depth article regarding the art of the long takes which you can read here. Basically, the long takes feature difficulties in almost any aspect (cinematography, administrative, mobility on locations, and more). Thus, long takes have to be planned to the small- micro details. There is no chance of executing long takes spontaneously and without any meticulous preparation. But what can be defined as a long take? According to Wikipedia, a long take is a shot lasting much longer than the conventional editing pace, but what defines a “conventional editing pace”? That’s a valid question no one can answer. By the way, editing is the most simplified part of the process because the editor takes the long clip and embeds it in the timeline:-) There were short films shot entirely on one take, so you can imagine the reduced work that the editor had.

1917: A film based on a Long takes

After explaining the tip of the iceberg of the complexity of the long take, you can now imagine the challenges of 1917 production in executing them. 1917 was filmed and edited to play as one continues shot over its 120 runtimes. As stated by Deakins: “You get further and further into a take, and it’s like six minutes, seven minutes, so you think that’s a perfect one and I’m looking at the sky and if the sun comes out we’re screwed…. it gets more stressful as the shot goes on, but when you get it’s like such a high”. Furthermore, according to Deakins, the end of one-shot is the beginning of the other one, which made this film a continues shot. There are a lot of hidden cuts in the film. For instance, check out minute 7:25-7:26 in the interview to explore one of the hidden cuts.

You get further and further into a take, and it’s like six minutes, seven minutes, so you think that’s a perfect one and I’m looking at the sky and if the sun comes out we’re screwed

Roger Deakins CBE, ASC, BSC

ALEXA Mini LF: The camera behind 1917

The camera system used in 1917 is ideal for capturing large format long takes. Roger Deakins CBE, ASC, BSC, was the first to receive a working prototype of the ALEXA Mini LF. In 1917, Deakins utilized the ALEXA Mini LF together with ARRI Signature Primes, and ARRI TRINITY camera stabilizer system (operated by Charlie Rizek) to get those dramatic long shots, by using the large format look and natural light, to make it as realistic as possible.

Large format in long takes cinematography

Using a large sensor in long takes is more complicated compared to Super 35. The DOF (Depth of Field) is larger, which means you have to calculate more precise the framing to avoid unwanted objects in the shot, especially in large production and crew. That’s even more complicated in dynamic shots, like in 1917. Furthermore, this challenge is multiplied when long shots are performed. However, when you nail it, you get the most realistic shot possible, due to the large format characteristics and advantages compared to Super 35, for instance.

ARRI offers certified training dedicated to its large-format camera system, which you can take online here. Also, you can read our in-depth review of ARRI Certified Online Training for Large-Format Camera System. The course is focused on tools and techniques regarding large format cinematography.

Take ARRI Certified On-Line Course for Large Format Camera System

Watch the interview below, in which Deakins sat down with Rotten Tomatoes to break down the most challenging assignments of his career.

Final thoughts

This is the first time we see a film based on long takes that were performed in large format cameras. Executing that project on a large scale production was quite a demanding task with a lot of hard work to accomplish perfection. However, the results are stunning, and I advise you to go and see it on the big screen.

[…] Lawrence Sher is a first-time nominee. The prediction is that 1917 will win. We wrote a couple of articles regarding 1917 and what makes this film so unique from a cinematography point of view. Furthermore, […]

[…] written an article regarding the utilization of the Mini LF and Signature Prime on Roger Deakins 1917. Read more about […]

[…] CBE, ASC, BSC, was the first to receive a working prototype of the ALEXA Mini LF. In 1917, Deakins utilized the ALEXA Mini LF together with the Signature Primes, and ARRI TRINITY camera stabilizer system […]

[…] new:-) However, we’ve covered this technique in dedicated articles so feel free to read them (Roger Deakins Explains the Cinematography Challenges Behind 1917, and 1917 Movie Review: One (Too) Long (Boring) Take in an Overrated […]